This study examines 1 the social, political, and mythical context of nascent Christianity in the eastern Mediterranean during middle Classical Antiquity—a context which drove the formation of new social groups centred on a new mythology. Three drivers for this new social activity are identified as:

In tandem with these social drivers, certain attributes of the new Christian mythology enabled it to compete effectively in the prevailing rich mythological ecosystem of the time and region. Still, important dogmatic contentions, ambiguities, and unfulfilled apocalyptic expectations forced many early Christian communities to re-evaluate the roles of Jesus and the Holy Spirit. Christian eschatology thus shifted dramatically during the first four centuries, cementing a sharply dualistic conception of reality—a conception which persists today.

- The disruption of conventional ways of life brought about by a rich ethnic, cultural and ideological heterogeneity.

- The appeal of Jesus to both Jewish monotheistic and gentile pagan sensibilities, albeit for subtly different reasons.

- The decentralisation of Judaism arising from the political clash between Jewish nationalism and Roman imperialism.

By examining these social forming and mythmaking impulses of the Christian communities in the first few centuries, certain cognitive challenges have been identified. These challenges should give a consciencious contemporary Christian thinker pause.

Firstly, Jesus' failure to provide dogmatic clarity on his divinity and messianic status remained a lingering dilemma, causing much dissention. The version of Christianity which emerged was therefore not due to unequivocal evidence nor to dogmatic viability. How then can Christians be sure that their faith is suitably aligned?

Secondly, Christianity's shifting eschatology inevitably relegated Jesus' role to the historical one of facilitating the Doctrine of Justification for humankind's salvation. In turn, the role of the Holy Spirit in mediating human affairs was elevated. However, the complexion of Christianity's proselytism through history portrays a role for the Holy Spirit which is sometimes gently persuasive, sometimes insidious and coercive, and at other times impulsive and extravagent, often accompanied by episodes of cultural insensitivity at best, and violence at worst. Attempts by Christians to retain the sanctity of the Holy Spirit by either ignoring the complexion of this role, or by shifting accountability away from the Holy Spirit and on to the faithful followers, can be regarded as insensitive or ignorant.

Thirdly, a dualistic Christian conception of reality endures which is starkly polarised and simplified along many axes. This has resulted in an artificial and ambiguous compartmentalising of human existence into body, mind, soul and spirit. There is empirical evidence for the existence of body and mind, but not for soul and spirit.

To understand the reasons for the emergence of Christianity in all its forms, why people invested in it, assuming new personal and social identities, why some came to believe the mythic claims at the core of the creed, and why certain kinds of Christianity won out over others to influence fifteen hundred years of Western culture, we need to reconstruct the history of the many groups that formed in the wake of Jesus and ask about their ideas, activities, and motivations. — Burton L. Mack[2]

Part of the old Via Raetia Roman road between Garmisch-Partenkirchen and Mittenwald in the Alps of southern Germany. The road was constructed between 195 and 215 ce during the reign emperors Septimius Severus (145–211 ce) and Caracall (188–217 ce) when Christianity was in its infancy. The spread of Christianity through Europe was due in part to the Roman communications network. She walks the road and looks back, as if reflecting on how ancient past contexts have shaped the present.

Two terms adequately express my own stance as

it pertains to this work. The first term is

metaphysical naturalism.[3]

It holds that natural elements, principles, and relations of the kind

studied by the natural sciences—including

mathematics—offer the only

ontological foundation for reality. In addition,

I hold that empirical observation combined with creative

reasoning offer the only reliable epistemology. Therefore I

reject the Hand of the Gods

as a supernatural

influence on reality insofar as the Gods are deemed

exogenous to the natural elements, principles, and

relations. Correspondingly, in my epistemology, I must

reject the Voice of the Gods

as a source of insight.

I chose monism[4] as my second term because it reflects my conviction that dualism is false and artifactual insofar as it describes the ontology of reality. I know of no reliable evidence with which the existence of a transcendent meta-physical deity may be educed. Admittedly, our rational and empirical endeavours—particularly those at the intersection of mathematics and physics—show that reality is paradoxically richer and simpler than meets the eye. But the richness and simplicity are profoundly immanent, wherein simplicity obtains richness. And neither point unequivocally to such an abovementioned deity.

I declare this to be my own work, entirely. In particular, no AI was used in any research, analysis, synthesis, writing, nor typesetting of this work. In short, AI was not recruited at any time in this work. Errors and inaccuracies are therefore proudly my own. But thank you, Mels, for your critical proofreading.

I dedicate this to my dad, Paul Herbert Kotschy (1933–2019). He taught me that it is nice to know things, and that perhaps the greatest value of knowledge is not that it enables things to get done, but rather that it offers enlightenment and informs context.

Humans are social beings. We tend to think, live and work in groups, from the basic family unit to the political nation state. We form networks of social groups within which we may articulate and activate our ideas, ideals and interests. And our myths. A sort of safety in numbers seems to be at work here. Perhaps it is because like-mindedness is comforting and efficient.

It is the same with our religions. For it is within our network of churches, synagogues, mosques and temples that the myths which we hold so dear are expressed, affirmed and propagated, almost always with little regard for their empirical and rational coherence and viability. Many may share my surprise that these networks exhibit such resilience, and that the menu of available myths is so varied. Indeed, this variety comes despite the profound eschatological significance we attach to belief, whatever these beliefs might be, and despite the obvious immiscibility between many of them.

Whence came such resilience of network and variety of myth? The answer, fundamentally, must relate to our collective need for self-actualisation. This need motivates the quest for meaning and purpose in a material world which to many seems devoid of such.

But perhaps more prosaically, the answer can be found by examining context. All events in history have context. And any attempt to understand the practice of social formation and mythmaking—a practice we call religion—depends in part on understanding context. For it is only through an understanding of the influences, motivations and impulses of people in earlier times and places that we may begin to know how things unfolded and came to be as they are. Context matters.

The focus of this study therefore is:

There is nothing dry about Christian mythology. An impersonal and abstract deity is made tangible, humanlike, and personable. The single Judaic godhead is reconceived as a triple, whilst simultaneously retaining a singular character. The triple is named the Trinity.2

Members of the Trinity are endowed with relational hierarchy, kinship, gender, and morality. One member of the Trinity, named the Son of the Father, was for a relatively short time incarnated as a human male here on Earth, abiding in cohabitation. His own human sacrifice was planned by the Trinity but was carried out by the humans.3

The Son's human life was punctuated by surprising events. These events belie predictable natural order:

A profound tension persists—a struggle, if you wish—between the Trinity and Satan over the providence of humans. This struggle concerns humans alone, beginning now and proceeding after death. Curiously, it does not concern other animals nor plants.14 Both the calibration and currency of the struggle is individual human morality. Satan, the ontology and unfolding of the struggle, and the cosmos in which humans are embedded, were all created by the Trinity, either for its self-edification or to obtain some form of relational connectedness with the humans.

Humans have been endowed with two special components of existence with which they may participate both in the struggle and in obtaining relational connectedness with the Trinity. These components are called the soul and the spirit. Whereas the human body and mind are ephemeral and more or less sensible, the soul and spirit endure and are ethereal. Admittedly, there is ambivalence over the existence of the human spirit, but the soul must exist as a necessary eschatological agent.15

Aspects of the nature of the Trinity, Satan, the cosmos, the struggle, and of its calibration and currency have all been codified in a canonical text known as the Bible. The Bible was written by fallible humans on behalf of the infallible Trinity. That is, the Bible is a sort of game rulebook written by the game itself. There is sufficient semantic ambiguity in the Bible that many foundational aspects of the abovementioned struggle have been rendered space and time dependent, based largely on how people interpret the Bible for contextual relevance.

Many Christians today are comfortable with this ambiguity,

happy to acknowledge that there are different ways to

interpret the Bible, that the boundary between literal and

allegorical content is diffuse and fluid, and that some of

its content must be discounted as being irrelevant.

However, despite its anachronism, ambiguity and

ambivalence, many regard the Bible as the divinely inspired Word of God,

applicable to all peoples regardless of their culture,

heritage, predisposition, and proximity.

Few would argue against the impressive investment in this mythology by a multitude of people variously spread around the world over the last two thousand years. From the earliest messianic Hellenistic Jews in the eastern Mediterranean region, the gentiles in Syria and Asia Minor,16 the aristocracy in the Roman and Byzantine Empires, the kings and monks of Europe in the Middle Ages, the Christian evangelists of Africa and South America during colonisation in the Renaissance period, the moral and economic protagonists of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, to the socially conservative Bible Belt evangelicals in an ostensibly secular and humanist North America, the Christian mythology has been ever so tightly woven into the tapestry of Western heritage.

Many may share my surprise over the depth and durability of the West's investment in the Christian mythology. My own surprise is due in part to the intricacy of the mythology itself, to its ostensibly humanlike character, and to ambiguity in many of its foundational tenets. On face value, the mythology implies a complex dualistic cosmology comprising an ethereal spiritual realm and a sensible material one. Humans are deemed to straddle both realms in ways which are sometimes arcane, sometimes facile, always ambiguous.

Does this impressive investment reveal a Hand of God working through the ages to promote Christian cosmology and eschatology, as per the abovementioned struggle? Or are there more mundane drivers for the investment which align with our innate quest for meaning and purpose in life, thereby creating impulses for new social formation and mythmaking? These important questions address how things came to be. So to answer them, it is essential to examine Christianity's various historical contexts. And perhaps the most important context is the time and place in which it all began, namely, Christianity's Jewish beginnings in the Near East during middle Classical Antiquity 800 bce to 600 ce.

Adaptability is an important attribute for survival. As exogenous variables undermine us, we adapt, either to eliminate the variables or to profit from them. This is no less so during times of social turbulence or isolation. To cope in these conditions, societies in the Near East did what societies do everywhere: they adapted by creating new social formations and by engaging in mythmaking. I am grateful to Burton Mack for showing me this.[8] In this section, I examine how the first of these two responses helped to propel Christianity from its parochial and fluxional beginnings to become a dominant institutional religion of today.

Classical Antiquity (800 bce–600 ce) was a period in which the ancient Greek, Seleucid, Ptolemaic, and Roman civilisations interlocked, producing a flourishing mix of societies, wielding great influence throughout Europe, North Africa and Western Asia. The arts, philosophy, educational ideals, and public dialectic of the ancient Greeks were imitated, preserved, spread, and ultimately eclipsed by the Romans over the wider region. It was a time of creativity and experimentation brought about by an exposure to a rich cultural diversity and a multiplicity of ideas circulating within common geographical regions.[9] Jesus and Paul of Tarsus were both exemplars of the time. Paul was Jewish by birth, Roman by citizenship, and Greek by culture.[10] (More on Jesus below.)

But it was a time, too, of disorientation. For syncretistic Hellenistic life in the eastern Mediterranean region was also characterised by ethnic tension, cultural clashing, political intrusion, and social upheaval. For the Jewish nation, this peaked during the 1st and 2nd centuries ce.

During the Second Temple period (516 bce–70 ce) Jewish culture, religion and administration was centred at the Jerusalem temple located in Judaea.[15] The temple was much more than simply a centre of worship. It was the icon and institution of a centralised theocracy. It enabled a two-tiered social stratification in Jewish society. The first was lead by the king and was the tier of national power, authority, and governance. The second was lead by the high priest and was the tier of propriety, purity, law, and worship. This two-tiered system offered everyone a Jewish identity and a sense of purpose.[16] The temple announced national pride. It served as a cultural monument. It connected people with their deity, enshrined an ideological separation as God's chosen people, and offered necessary professional services as the state's civic centre. In short, the temple was the binding glue in the model of a centralised autocratic temple-state—a model which had worked for many centuries.

So why change it? Because there was exposure to another model.

The Hellenistic influences in the region exposed people to a different type of state: the Greek city-state. Following the conquests of Alexander the Great (356–323 bce) the Seleucids had established about thirty-five Hellenistic towns in Roman Palestine by the time of the First Jewish-Roman War. These city-states enjoyed relative freedom in citizenry and autonomy in governance and culture.[19] People living in or near such city-states would have had exposure to Greek styles of pedagogy, debate, discourse, public display, and private life.17 For example, Philo Judaeus, living in Alexandria Egypt (circa 20 bce–50 ce), was a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher. Extant copies of his writing reflect his intended symbiosis of Jewish theology and Hellenistic thought.[22][23]

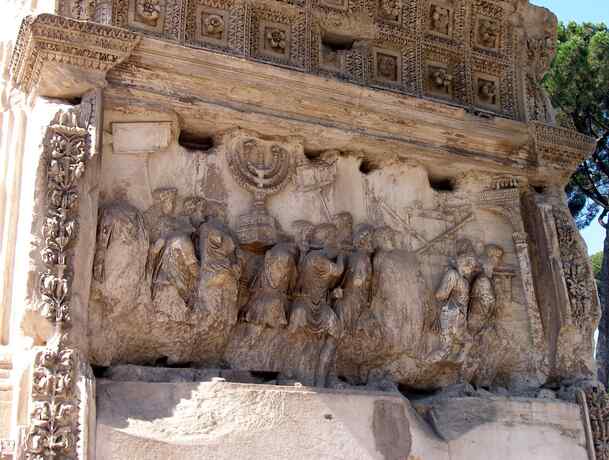

In 6 ce, Rome declared Judaea a province under direct Roman administration. Sixty years later, spurred on by a tenacious Jewish nationalism, the First Jewish-Roman War (66–73 ce) was fought. During the siege on Jerusalem in 70 ce, the Second Temple was destroyed by the Romans. And again, about sixty years later during the Bar Kokhba Revolt (circa 131–136 ce), the Romans inflicted a humiliating defeat on a group of Jewish separatists lead by Simon Bar Kokhba.[24]

The Roman Senate and People (dedicate this) to the divine Titus Vespasianus Augustus, son of the divine Vespasian.

Amidst this political upheaval, Jewish nationalism was vanquished. Expatriated from their Judaean homeland and from Jerusalem in particular, the Jewish people were made to endure economic hardship and religious persecution. Judaism was in flux. The model of a centrist two-tiered theocratic state, centred on the Jerusalem temple, and which had defined the Jewish nation for centuries, was now in tatters. The model was replaced with a decentralised collection of progressive city-states, subject to foreign rule, and open to the pluralism of paganism.

These two models of state, namely the Jewish temple-state and the Greek city-state, presented an important ideological faultline for the Jewish people. A decentralised, democratic and multicultural national ethos conflicted with a more centralised, autocratic and culturally homogeneous one. Importantly, New Testament records of Jesus' teachings reflect that he was well aware of this faultline.

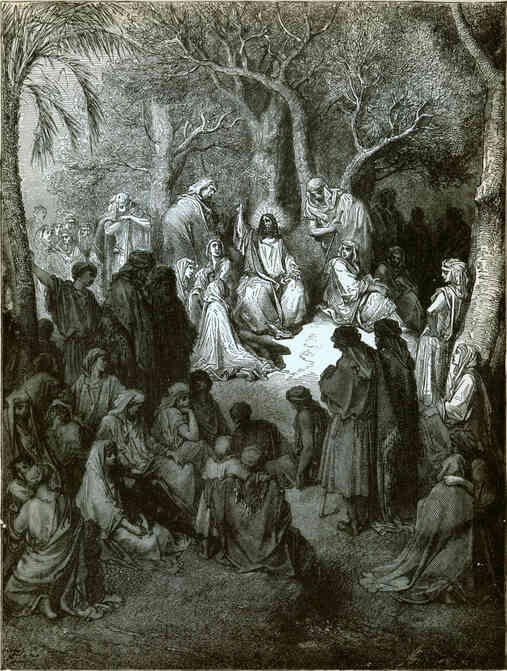

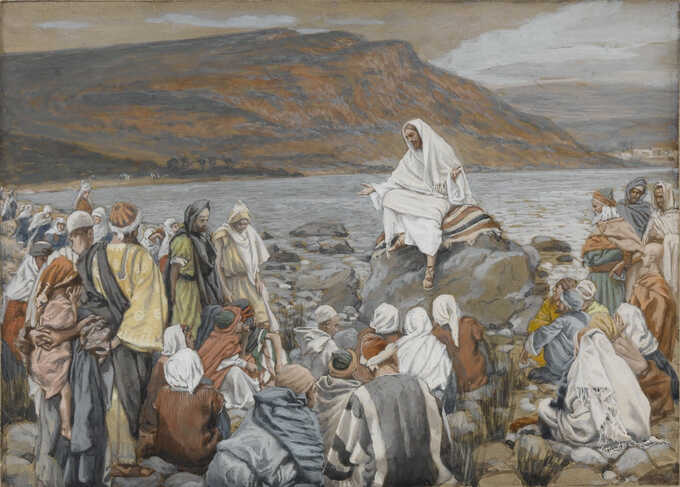

Jesus grew up in Galilee. The region in northern Israel known as Galilee was an important centre for Judaic tradition. Galilee was not culturally and politically isolated from the wider world. Communities in Galilee were likely susceptible to Hellenistic influences. It was a centre of relative affluence. Recent archaeological discoveries of synagogues from the Greco-Roman period indicate Roman cultural influences there.[26][27][28] People were familiar with the Greek language owing to the strategic placement by the Romans of Hellenistic towns along the Jordan River.

During Jesus' time, there were no fewer than twelve such towns located less than twenty-five miles from his hometown Nazareth in Galilee.[29] It is therefore very likely that Jesus was raised as a Hellenistic Jew. He would have aligned with a culture somewhat distinct from that of the orthodox Jews living further south in Judaea and especially in Jerusalem where the Jewish temple was located. So it is not surprising that in the eyes of many, including the orthodox Jewish establishment, Jesus' message was at once intellectually adventurous, individually progressive, and culturally inclusive.

But Jesus was also a religious Jew. And as a Jew, his message espoused individual piety and a regard for a Kingdom of God. So on the one hand his work and life reflected the syncretistic social impulses of the region, while on the other he was a charismatic religious leader, who like all such leaders sought to amass a following. And this he did in Galilee.

Within Jesus, the ideals of the Greek city-state and of the Jewish temple-state collided and became hybridised. Jesus' innovative and progressive mindset was able to confront an old and conservative one without completely discarding his religious heritage. Simply put, with Jesus lay the potential for the creation of new social formations, and for the making of new myths centred on himself and his message of a Kingdom of God.

The earliest followers of Jesus were members of apocalyptic Jewish sects who believed that Jesus was their resurrected Messiah.18 Living in the 1st century, they like all Jews would have experienced the social and political turmoil of the time. It is therefore not possible to separate the social dynamics of the early Christians from that of the Jews. In fact, it was only in 301 ce when Emperor Constantine legalised Christianity in the Roman Empire that the vestigial links to Judaism were severed, allowing Christianity to become an ostensibly gentile religion.

For the Jews and the early Christian-oriented Jews, the devastating tumult of the first two centuries cannot be over-stated. The destruction of the temple disrupted the two centralised tiers of power and propriety. It brought to an end the organising of society in the model of an ancient Near Eastern temple-state, and it intensified the hope for a political messianic emancipation. But any such hope pinned on Simon Bar Kokhba was lost in the crushing defeat of the Bar Kokhba Revolt by the Romans.

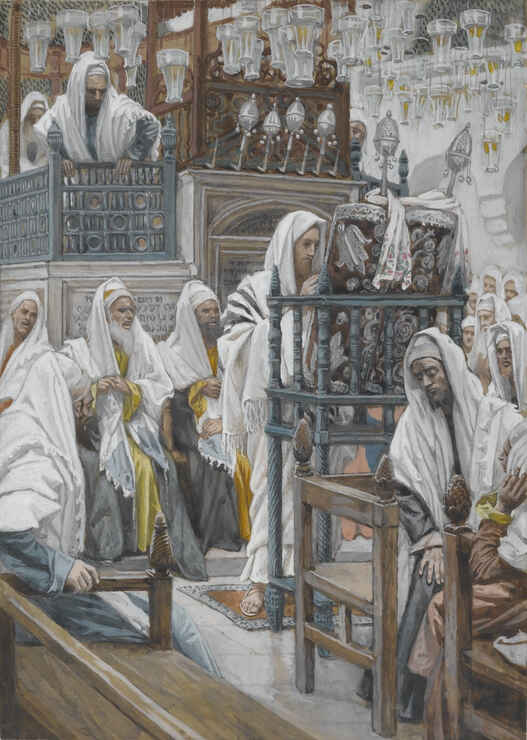

But the tumult had two positive spinoffs—spinoffs which would serve nascent Christianity well. Firstly, the two wars and the progressive Hellenistic influences helped decentralise the practice of Judaism. For the Jewish response over time was to rely more on a distributed network of gathering places at which Jews could contemplate and propagate their heritage. They formed synagogues (from the Greek synagoge), fellowships (koinaniai), festive companies (thiasoi), clubs (collegia), and Christian-oriented assemblies (ekklesia).[37] And without the constraints of a Temple centre to govern religious thought, creative thinking on the divinity of Jesus and his messianic status blossomed. Numerous Jesus movements sprang up, reflecting growing divergence of opinion over Jesus and the ontology of the Trinity.

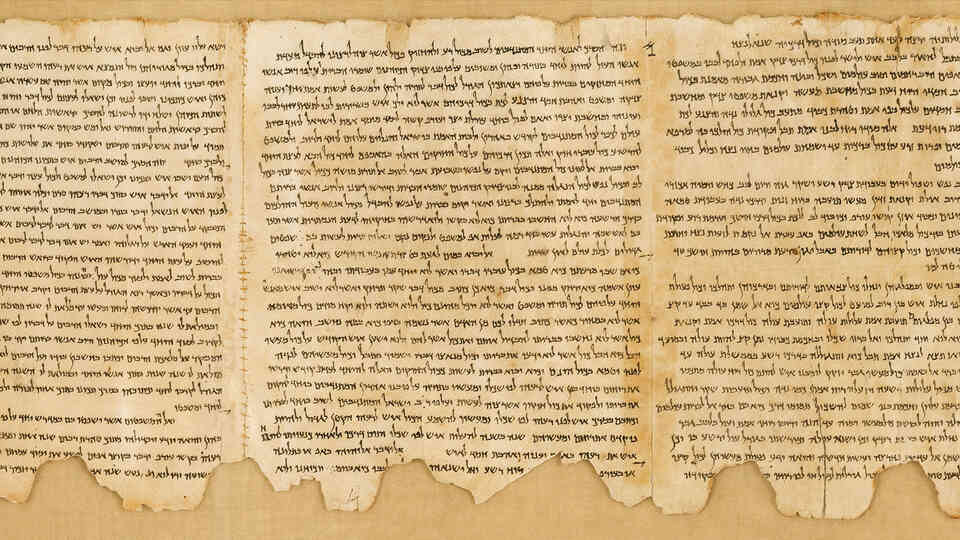

The second spinoff was that there was a shift from an oral tradition to a written one. Pharisaic Judaism and a Jewish code of conduct had been taught orally at the Second Temple in Jerusalem, encompassing rituals, worship practices, interpersonal relationships, God-man relationships, festival observance, and various legal matters. After the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, and especially after the upheaval and expatriation of the Jews from Judaea, the oral tradition could no longer be maintained. This threat to the very survival of Jewish identity and heritage provided a necessary impetus for rabbinic discourse to be recorded in writing[38][39][40] And the early Christian-oriented Jews would have had to adapt just like other orthodox Jews.19

After the Bar Kokhba Revolt, the effort to codify in written form the Judaic tradition was moved out of Judaea to academies in Tiberia, Sepphoris, Caesarea and Usha, all located in or near Galilee.[41][42] And the use of Koine Greek and Latin as languages replaced Biblical Hebrew.

A side effect of this migration from an oral tradition to a written one was that ideological differences between early Jewish Christianity and early Rabbinic Judaism became formalised and codified. These differences included: the messianic status of Jesus, the relevance of the Torah purity laws, the broadening of God's covenant to include gentiles, and the theological interpretation of the destruction of the temple. Rabbinic Judaism saw the destruction of the temple as God's punishment for neglecting the Torah. The early Christians however saw it as punishment for Jewish rejection of Jesus as a messiah. The early Christians believed that God had replaced the old covenent with Israel centered on the temple with a new covenant centred on Jesus and with nascent Christianity metaphorically the new Israel.

Christians often use the rapid early spread of Christianity in spite of the burden of persecution as evidence for the veracity and viability of the early new faith. Prosperity in the face of adversity must count for something, they claim. They also often claim that the Holy Spirit assisted the early proselytisers in spreading the new faith, in accordance with Acts 1:8.

However, these claims are too simplistic, for two reasons. Firstly, they fail to acknowledge the motivations for the persecution. The early Christians were persecuted not specifically because of the content of their ideology, but because of their ideology's strong association with Judaism. That association served to immerse the early Christian-oriented Jews into the intense socio-political conflict between the Jews and the Romans during the first two centuries. Faced with the extreme rancor of the conflict, it is hard to imagine the Roman persecutors selecting against subtle ideological differences between the growing number of Judaic sects, some of which were Christian-oriented sects.

Secondly, the claims ignore the ideological context into which the new religious message was being disseminated. The boundary between Judaism and early Christianity was diffuse, with the latter regarded as a new form of Hellenistic Judaism.[44] The initial appeal to the Hellenistic and Roman pagan world in Syria, Asia Minor, and around the Mediterranean was therefore not for a Christian message per se but it was for a Judaic message. It was an apocalyptic Judaic message, endowed with a messianic figurehead and a personalised triune deity bearing some resemblance to respective local pagan deities.

The new message softened the hard austerity of the lonely Jewish deity, infusing it with humanlike personalities, kinship and corporeal body, not unlike the Greek gods of Zeus, Aphrodite, Hades, Apollo, and others of the time. This new form of Judaism was a sort of ideological midpoint between the strict monotheism coveted by the conservative Jews and the polytheism of the Greek, Roman, Parthian and Egyptian pagans. It is this ideological context in which a new form of Judaism, namely Christianity, found its appeal and which therefore helped it to spread, persecution notwithstanding.

This study of the context of Jewish societies in the eastern Mediterranean during middle Classical Antiquity has revealed three drivers for new social formation in early Christian communities. They are:

New ideas were being discovered on how to live. The rich ethnic, cultural, and ideological heterogeneity combined with political intrusion in the eastern Mediterranean prompted creativity and an exchange of ideas. But it was also socially, culturally, and politically disorientating. This is exemplified in the collision of two models of state, namely, the Jewish temple-state of the south in Judaea and environs, and the Greek city-states of the north in and around Galilee.

Conventional ways of life were being disrupted.

The singularly unique charisma and rhetorical skill of the Hellenistic Jew named Jesus, and his countercultural message of individual moral purity and multicultural inclusivity, appealed to Jewish and non-Jewish audiences alike. From Jesus was born a new form of Judaism which was sympathetic not only to the abovementioned heterogeneity, but also to the intense expectation of messianic emancipation, even though there were subtle but important differences attributed to Jesus' messianic status, as elaborated below.

In a sense, monotheistic messianic Judaism was being exported from the ethnic Jew to the multicultural pagan gentile, and the mythologically appealing nexus was somewhere in between.

Politics liberalised Judaism. The political clash between Jewish nationalism and Roman imperialism in the first two centuries lead to a loss of Jewish cultural moorings and to widespread displacement from Jewish homelands. But instead of this extinguishing the practice of Judaism, it merely decentralised the practice, spurring regional ideological creativity, and prompting an important shift from an oral tradition to a written one.

The new myths as distinct from orthodox Judaism were thus being formalised, codified, and in time canonized.

But how did the new Christian myth which underpinned this new social formation square up against other prevailing myths in the Near East? What was its contextual appeal? And how did the various inflections of the new myth become consolidated?

The previous section examined the conditions of social turbulence and isolation experienced by Jewish communities in the Near East during middle Classical Antiquity. The conditions prompted two natural responses within the communities. The first response was to engage in new social formation, as elaborated in the previous Section. And the second, as identified by Burton Mack, was to create new myths.[45]

The mythological ecosystem of the eastern Mediterranean region during middle Classical Antiquity exposed Judaism and its offshoot Christianity to much competition. The Greeks, Seleucids, Egyptians, and Romans each had their pantheon of gods, along with their epic tales of the intersection of humans with the gods.

Unsurprisingly, their respective deities were almost always endowed with humanlike character. And in the naïve and superstitious pagan mind, it seemed sensible to link the unfolding of natural events to the will of the gods, sometimes capricious and at other times refractory. The acts of the gods, such as the cycles of the sun and moon, seasonal changes, the abundance of rain, the prevalence of disease, and crop yields, all amply reflected the presence of the gods and of their interventions.20 Sacrifice of possesions, of animals, and sometimes of humans, was carried out to demonstrate human fielty to the ruling gods.[46]

But just as the gods were humanlike, so too were many humans godlike. Egyptian pharoahs were attributed divine powers by virtue of their position in society. They acted as intermediaries between (wo)man and god. In ancient Greek mythology, the legendary founder of the Perseid dynasty, Perseus, was the son of the god Zeus and the mortal Danaë.[47] In ancient Roman mythology, Romulus and Remus were twin brothers whose mother was Ilia Silvia,21 a vestal virgin.2223

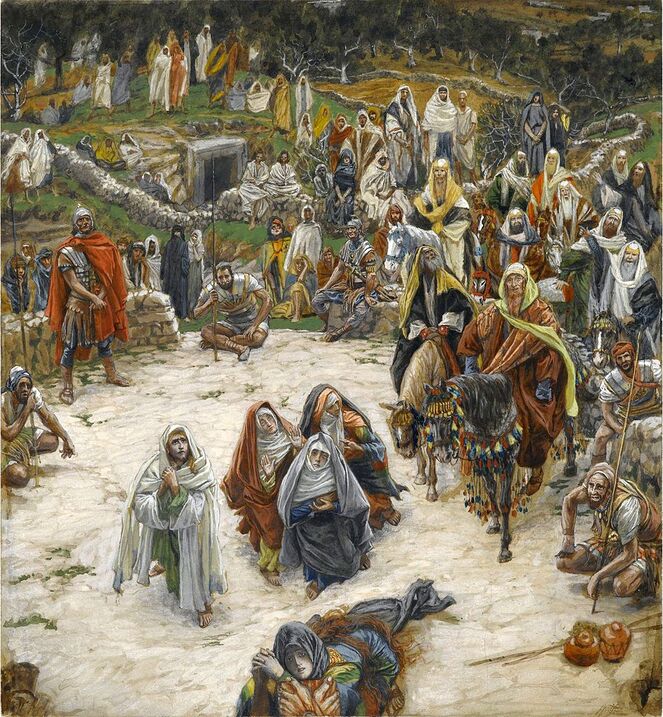

In 41 ce Livia Julia, the wife of Caesar Augustus, was deified posthumously. Numismatics tells the tale, for achaeological evidence exists of coins minted by Philip Herod bearing that date, and with iconography on the coins attesting her divinity.[49] Soon thereafter, the divinity of Emperors Vespasian and his son Titus was recorded in a prominent inscription on the Arch of Titus constructed in 82 ce (Refer above to the photograph of the arch). What is significant about this evidence regarding Livia Julia and Emperors Vespasian and Titus is that around the time of Jesus, at least three real people other than Jesus were considered divine.

During the first four centuries of Christianity, Mithraism emerged as a chief rival in the Near East. Mithraism was practiced in the Roman Empire between the 1st and 4th centuries ce. It was centred on the god Mithras. After the earlier defeat of the Persians by Alexander the Great, worship of Mithras spread from Persia through the Roman Empire. As the god of Light, Covenant and Oath, Mithras was the counterpart to the Greek sun-god Helios and the Roman god Sol Invictus. It was believed that Mithras was miraculously born from a rock. The religion was eventually officially decreed heretical and suppressed by the Christian establishment.[50][51][52][53]

Manichaeism, too, was once a major religion. Starting in the 3rd century ce, it spread rapidly, rivalling Christianity and Islam in geographical extent and cultural influence. It had its roots in local Mesopotamian religious movements and in Gnosticism.[54][55] Indeed, the celebrated early Christian thinker and writer, Augustine (354–430 ce), converted from Manichaeism to Christianity in 387 ce. His conversion re-infused early Christianity with a strong dualistic sense which was informed by Manichaeism's mystical elements.[56][57] Due to intense persecution and vigorous attack by Islamists, Buddhists, the Christian Church, and the Roman state, the Manichaeism religion almost disappeared from western Europe in the 5th century, from the eastern portion of the Roman empire in the 6th century, and from China in the 9th century. To be sure, the motivation for the persecution and attack was not political. It was ideological and religious.

The monotheism of Judaism was yet another competitor in the mythological ecosystem of middle Classical Antiquity. And from it emerged the new form of Hellenistic messianic Judaism centred on Jesus. As a Jewish social movement, the new Judaism was readily accepted within the Jewish diaspora of the eastern Mediterranean. As the new Jewish messiah, whose promised return was considered imminent, Jesus re-asserted God's covenant with the Jewish people. Actually, Jesus asserted a new covenant. Not only would God's former convenant with Israel as God's chosen nation be re-established, but through his resurrection, exultation to heaven, and subsequent return to Earth, Jesus would usher in for the Jews an apocalyptic Kingdom of God on Earth, thereby vindicating Jewish nationalism. Jesus thus offered new hope and practical relief for a fractured Jewish nation. However, as months turned to years, and years to decades, it became increasingly clear to the Christian-oriented Jews that Jesus' return to Earth was not imminent. And so, over time the fervent hope placed in Jesus as the messiah waned, and by the 5th century the Christian Jewish movements had fizzled.

But by then the horse had bolted. For by then,

the new messianic Judaism had also been readily

accepted as a gentile social movement, even though

the gentiles had very different messianic

expectations than the Jews. Messianic Judaism

offered the multicultural pagan a more humanlike

and multipartite version of austere Judaic

monotheism. The complex and sometimes confusing

collection of pagan demigods was simplified and

consolidated into the single humanlike man-god,

Son of Man, Son of God, Jesus. Jesus was not

unlike other Greek divine men, the sons of God

endowed with supernatural power to perform healings,

exorcisms, changing of natural events, and other

wonderful deeds. Jesus was a new talisman, conjuring

a tangible connection between the ethereal

transcendent world of the gods and the sensible

concrete world of humans.

But in the unfolding new mythology, the nature of this connection between god and human took on different forms as people grappled with who Jesus was, whence he came, what his role was, what the Holy Spirit is and what its role is, what the Kingdom of God is, and what we as humans must do. Thus, from the time of Jesus onwards, there has been ample scope for contention within the Christian myth itself.

Ironically, the most foundational tenet of the Christian myth, namely, the nature of the divinity of Jesus, was also its most contentious.

Christianity's first four hundred years witnessed the

spontaneous formation of networks of social groups centred

on the new myth (as discussed above in

Section New social formations in the Near East

.

But the myth itself was in flux and susceptible

to splintering. The early Christian-oriented Jewish

groups could not agree over the relevance of and

adherence to the Torah purity laws. Nor could they

agree on the definition of God's covenant. Was Jesus

the messiah for Israel's Jews alone, or for Jews and

gentiles everywhere?

In fact, who was Jesus? The Ebionites, for example, were orthodox Jews who regarded him as a messiah, but they most likely rejected his divinity and his miraculous conception.[59] The Nazarenes held similar beliefs and practices but accepted the miraculous conception.[60] Numerous other Christian movements sprang up reflecting much disagreement and dogmatic variability.

Gnosticism is a contemporary term for a variety of religious mythical ideas originating in the Jewish-Christian milieux in the 1st and 2nd centuries ce. In 1945, thirteen leather-bound papyrus codices24 buried in a sealed jar were found by a local farmer living in upper Egypt near the town of Nag Hammadi. The writings in these codices comprise 52 early Christian Gnostic texts. It was a significant archaeological discovery because it opened a window into more mystical and at times allegorical interpretations of the life, role and divinity of Jesus, and the Kingdom of God at that time.25

Early reflections on the divinity of Jesus followed two broad themes.[61][62] In the first theme, Jesus pre-existed before his physical incarnation. As the eternal Son of God, he possessed unity with the Father in the heavenly realm before, during, and after his incarnation. Therefore, as the Son, the status of Jesus' membership in the Trinity was equal to that of the Father and the Holy Spirit. In the Son is embodied the Platonic Form[63] of Love, even though the Son was incarnated as Jesus the man.26

In the second theme, Jesus did not pre-exist prior to his

birth, but was begotten—or adopted

—by God

to become his divine Son. His deification occured

either at birth, at his baptism, during his

resurrection, or after his final ascension. Here,

in the exalted form of the Son, the divinity of

Jesus is subordinate to—and

ostensibly distinct from—that

of the Father, because the Son was created by

the Father. The Son came into existence as a particular

of the Platonic Love Form. But at the instant of

deification, the Father elevated that particular to

be the Form itself.

While the first theme maximises the divinity of Jesus as a deity having no spatio-temporal origin, it profoundly complicates the monotheistic Judaic godhead by having to accommodate two extra deities, namely, the Son and the Holy Spirit. Conversely, the second theme endows a mere ordinary man with divine attribute, thereby assigning a divine figure a curiously arbitrary spatio-temporal origin. But the second theme retains the compact simplicity of the monotheistic godhead.

This lingering dilemma over the divinity of Jesus came to a head in the 4th century. Two ecumenical council meetings of Christian bishops were convened in an attempt to resolve it. The first meeting took place in 325 ce in the city of Nicea, Anatolia (also known as Asia Minor).[66] The so-called Nicene Creed was adopted, and belief in the second theme under the guise of Arianism[67][68] was declared heretical.27

However, Arian Christianity persisted, prompting a second council meeting in 381 ce in Constantinople. Later, Arian Christianity was considered correct and Nicene Christianity heretical. Nicene Christianity finally eclipsed Arian Christianity during the 7th century ce, and the modified creed which was adopted became known as the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed.[71]

It is puzzling how, for a religion which rose to such worldwide prominence, deeply foundational aspects such as the nature of the divinity of Jesus remained unresolved and controversial for so long. Dogmatic support for both themes of Jesus' divinity was widespread in the first seven centuries ce. And in the ideological tug-of-war between Arian and Nicene Christianity, the ultimate victor could have been either. The victory of Nicene Christianity was thus more due to fluke and historical accident than it was due to evidence of the divine or to dogmatic viability.

Indeed, if adoptionism

were to have won,

and Arianism in particular, then the ideological

complexion of Christianity would have ended up

very different than it is today. Contemporary

Christians would be embracing a very different

belief in the divinity of Jesus. Christians are

either unaware of this persistent foundational

dilemma, or they tacitly consider it unimportant

and simply ignore it.

Belief in the resurrection of Jesus convinced the early Christians in the 1st and 2nd centuries that Jesus was more than a mere mortal, that he was the divine Christ, and that the days of eschatological fulfilment were close at hand. They fully expected an imminent Second Coming of Jesus, heralding the arrival of the World to Come, but preceded by a period of rebelliousness and rampant evil. After the occurrence of the global apocalypse, the heavens would open to reveal God in his full glory, and the Christ would descend to Earth from heaven above to embrace and liberate the faithful.28

However, over time, the anticipation of this earthly apocalyptic transformation of reality became increasingly unfulfilled. Faced with the gnawing dilemma of the non-arrival of Christ, of the persistence of oppressive foreign Roman rule, of continued hardship through persecution, and of the apparent durability and viability of the natural material world, the eschatology of early Christianity drifted away from such rapturous divine intervention. Indeed, this growing awareness of the delay in the Second Coming already started to appear in the New Testament writings, particularly in John's Gospel.

To overcome this eschatological dilemma, emphasis shifted from a divinely mediated future new world order, to Jesus' past life and death on Earth, to individual piety and control of man's refractory will and desire, and to the presence and influence of the Holy Spirit. Increasingly, the role of Jesus in facilitating a destiny for mankind shifted to that which was already accomplished by Jesus, elevating his death to one of sacrifice—indeed, a final human sacrifice—followed by his resurrection. In turn, the Holy Spirit was seen to take on a more active role in human affairs, albeit a diffuse and ambiguous one. And the agency of the Holy Spirit was in and through the faithful rather than on and over the faithful.

By the 4th century, the anticipation of God's miraculous intervention in the natural world and in current affairs had waned. As the emperor of the thriving Roman Empire, Constantine's conversion enabled a dramatic shift in the eschatological expectation from that of the early Christian communities. For without persecution the psychological need for an immediate apocalypse diminished, and Rome's pre-apocalyptic role as the Antichrist was replaced with that of defender and extender of the faith.

Now as defender and extender, the structure and culture of the Roman state combined with the Judaic monotheistic tradition to impute a distinct character to the early Church, namely: a belief in the Doctrine of Justification;29 an alignment of human wills and desires to that of the Church; a strong organisational hierarchy; and a centrifugal proselytising urge. And now, working in and through the faithful, the role of the Holy Spirit was to help extend Christianity's dogmatic influence on Earth—an influence firmly rooted in a strong earthly church.

A consequence of this eschatological shift was that accountability for the fulfillment of God's plan for the world shifted from God to human, from the Holy Spirit to the faithful. This shift was subtle but inexorable. While any apparent success in the unfolding of God's plan was easily attributed to the Holy Spirit's glorious intervention, any failure in the unfolding was now due not to God but to human weakness and blunder. This shift in accountability was necessary, because without it, the growing institutional church's dogmatic ediface could crumble. Without it, the notion of a perfect and inerrant Christian deity was difficult to sustain.

But the unfulfilled apocalyptic expectations of the early Christian communities, when combined with an enduring sense of hope through salvation, had another effect: to reinforce a spirit-matter dualism in the conception of reality. Increasingly, the Kingdom of God came to be seen as otherworldly, mystical, as a state of experiential bliss attainable only by embracing the Doctrine of Justification.

This material world was increasingly denigrated as

something from which the faithful must escape.

Indeed, the faithful are

in this world but not of this world.

Humankind was infected with an inherited Original

Sin, and so languished in a fallen and sinful

state. Arguably subtle concepts of good and evil,

love and hate, creator and created, heaven and

hell, and physical and metaphysical, were all

polarised and simplified.

The existence and durability of the soul was emphasised as the exclusive participant in the metaphysical otherworld after bodily death. As the influence of the Christian deity shifted from the tangible and physical to the intangible and metaphysical, the providence of the soul moved centerstage.

This eschatological transition was codified in the writings of Augustine after his conversion from Manichaeism in 387 ce. Living during the death throes of classical civilisation, facing the decline of the Roman Empire, Augustine viewed the present world as inherently evil. Yet the salvation solution he identified was not an apocalyptic renovation, but rather a redemption of the soul through salvation, as enshrined in the Doctrine of Justification, and as promoted through ascetic piety.

Thus, over time, the Christian anticipation of an imminent glorious End Time was substantially weakened, and disappeared as a dominant motivating force. Nevertheless, contemporary Christians do seem to countenance a Second Coming followed by an End Time, but neither of which is imminent nor essential to the salvation of the soul.

The result of this dualism was that the physical and metaphysical realms became sharply delineated. To accommodate this delineation, conceptions of the individual's self-conscious existence became ever more compartmentalised. Body, mind, soul, spirit. Body and mind are physical. Soul and spirit metaphysical. Indeed, this delineation and resultant compartmentalism persists in Christian ontological thinking to this day.

Exposure to Christianity's evolving mythological content and to its dramatic and eneluctable eschatological transitions presents the contemporary consciencious Christian with challenges.

It may be difficult, even painful, to accept that many cornerstones of Christianity's dogma and doctrine remained unresolved long after the departure of Jesus. Indeed, it is a curious fact that the central figure, Jesus himself, failed to provide necessary dogmatic clarity. If Jesus truly was an incarnated deity, singularly distinct from other mythological deities, having messianic purpose, and fulfilling a tragic and exultant destiny, then I would have expected greater precision from him in order to prevent centuries of disquieting ambiguity and dialectic conflict.

For eventually, by the time the four Gospels were

composed in the latter part of the 1st century, an

elaborate and at times inconsistent belief

structure had developed, involving remembered

facts of Jesus' life, his parables and aphorisms,

the young Church's didactic injunctions,

apocalyptic beliefs, gnostic influences, and an

arguably complex eschatology. Apart from the

Gospels, Paul's writings make up a large part of

the New Testament canon. Yet Paul never met

Jesus. And the texts which were included in the

canon are not always consistent and even contain

factual errors.30

Hence the Jesus that history came to know is the

Jesus recalled, reconstructed, interpreted, and

vividly imagined by writers of the New Testament

living one or two generations after the period

covered by their narratives. It is no wonder,

then, that the nature of the divinity of Jesus

remained controversial for so long (as elaborated in

Section Divinity of Jesus

).

Are we simply to accept that somehow a sufficiently accurate account of the role and divinity of Jesus emerged in the first four centuries such that our faith may be suitably aligned? Was it the work of the Holy Spirit to ensure that history's dice landed just right?

If the early Christians were so hopeful of Jesus' Second Coming, why then did it not happen? Were they somehow misguided? Some of the early Christian-oriented Jews lived contemporaneously with Jesus. And if they themselves were so misguided in such important matters of apocalyptic eschatology and the divine nature of Jesus and the Trinity, how can we be sure that we are not misguided today, two thousand years later?

Furthermore, given that the Second Coming did not occur when the Christian founding fathers expected it to, what degree of reliability can we attach to the holy texts, and especially to those parts which have any eschatological content? It seems we must simply once again apply our subjective and fallible re-interpretation efforts to the texts.

Many of my interactions with Christian believers confirm two things: firstly, a willingness to countenance such re-interpretations of the texts as is fitting; and secondly, an apparent ignorance that the vicissitudes of history have demanded such re-interpretation, and still do. While the re-interpretation effort conveniently renders the holy texts ever right and ever true, it exposes the obvious conundrum of an eschatology in transition.

Given the Holy Spirit's more active role as perceived by the faithful in extending Christianity's dogmatic influence around the world, we must ask about the work of the Holy Spirit thus far.

The selection of Christian writings to produce the canonical New Testament took place gradually during the first four centuries. During this contentious time, did the Holy Spirit work to ensure that the heterodoxical apocryphal and gnostic texts were appropriately filtered from the orthodox ones, thereby helping to compose the correct inspired Word of God? And during this time, did the Holy Spirit tacitly suppress a more pristine form of Christian monotheism which re-emerged in the 3rd and 4th centuries, as contemplated by Arius and (256–336 ce) others?[75] That is, did the Holy Spirit steer the debate between Arianism and Trinitarianism in favour of the latter, despite there being strong and broad support for both, and despite the vituperation and vitriolic censure from both sides of the debate, not just the losing side?

The historical evidence is overwhelming that a religion's proselytising urge is satisfied more through force, fear and military might than it is through gentle persuasion and the exegetic appeal of the religion's dogma. Unfortunately, Christianity is no exception here. Various violent episodes and impulses in its history have helped ensure the cultural and geographical dominance of Christianity in many parts of the world. Such episodes and impulses include:

Is this the work of the Holy Spirit? Sometimes gently persuasive, sometimes insidious and coercive, other times impulsive and extravagent. Has the Trinity, and the Holy Spirit in particular, initiated and manipulated these tragic episodes and impulses to help extend Christianity's dogmatic influence on Earth? Is this the wielding of power alluded to in Acts 1:8? After all, these episodes and impulses have been most effective. And if this is not so, then it seems that the work of the Trinity and the Holy Spirit must once again be the subject of our subjective and fallible re-interpretation of the holy texts.

This study examined the social, political, and mythical context of nascent Christianity in the eastern Mediterranean during middle Classical Antiquity—a context which drove the formation of new social groups centred on a new mythology. Three drivers of new social formation were identified as: 1. the disruption of conventional ways of life brought about by a rich ethnic, cultural and ideological heterogeneity; 2. the appeal of Jesus to both Jewish monotheistic and gentile pagan sensibilities, albeit for subtly different reasons; 3. the decentralisation of Judaism arising from the political clash between Jewish nationalism and Roman imperialism.

In tandem with these social drivers, certain attributes of the new Christian mythology enabled it to compete effectively in the prevailing rich mythological ecosystem of the time and region. Still, important dogmatic ambiguities and unfulfilled apocalyptic expectations, forced many early Christian communities to re-evaluate the roles of Jesus and the Holy Spirit as members of the Trinity. Christian eschatology thus shifted dramatically over time, cementing a sharply dualistic conception of reality. This conception persists today.

This examination of the social forming and mythmaking impulses of the early Christian communities has revealed cognitive challenges—challenges which should give a contemporary consciencious Christian thinker pause.

Contemporary adherence to the Christian faith seems largely to ignore the actual drivers for new networked social dynamism in the early Christian-oriented Jewish communities in Jerusalem, in Galilee, and in the diaspora. Some of these drivers were tangible and mundane. In our ignorance, it is just too easy to attribute the rapid rise of Christianity in the West to the Hand of God working to fulfil God's Plan, and then to make our personal feelings and predilections bear testimony to this.

The journey from Jesus, a Jewish man living in a syncretistic Hellenistic Galilee, to the institutionalised Nicene Christian religion of the 4th century and beyond, with its canonized charter texts of the New Testament and the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, was long and bumpy and twisty. The historical record of early Christianity clearly shows that although Jesus intended to start a new socio-religious movement, Jesus did not provide a lucid blueprint for an entirely new religion. At least, if he did provide such a blueprint, then his followers did not fully understand it.

It is perhaps surprising that belief in the ambiguous notion of a dualistic triune deity—a deity which includes the Son of speculative divine origin, and the Holy Spirit of nebulous character and dubious active agency—persists without due reflection on the actual drivers of Christianity's growth over time. Many of these drivers were prosaic, mundane, or both.

Contemporary belief seems to pay no heed to the competition in the mythological ecosystem of the eastern Mediterranean during middle Classical Antiquity. The belief tacitly acknowledges that out of the many different mythical ideologies which were competing for influence in the first four centuries, Christianity won. But it ignores that the fight for dominance was often acrimonious, at times brutal. Furthermore, the belief disregards the empirical evidence in history of how the religion's unrelenting proselytising urge was (and is) satisfied, resulting in its expansion. Stated candidly, to attribute Christianity's emergent dominance to the work of a Trinity, and the Holy Spirit in particular, may be regarded by some as naïve and fatuous at best, callous at worst.

The belief disregards that within nascent Christianity itself, it took no less than four hundred years for many of its ideological cornerstones to be laid. During that period, important aspects of the divinity of Jesus, the ontology of the Trinity, and basic Christian eschatology, were all in flux.

From the early unfulfilled apocalyptic expectations and with an enduring sense of hope through salvation, a strongly dualistic Christian conception of reality emerged, and remains till today. Consequently, the contemporary Christian conception is starkly polarised and simplified along many axes, resulting in an artificial and ambiguous compartmentalising of human existence into body, mind, soul and spirit.

What impels us to align our emotional and rational faculties with our respective faiths? Is it injunction (or coercion) from our collective kith and kin? Is it a supine dependence on the promise of an afterlife? Perhaps it's an emotional resonance obtained through a purported personal relationship with the divine, such as with Pentecostalism's Jesus as intimate Personal Saviour. Perhaps it's because our faiths are imputed to offer an immutable set of moral precepts bestowed by the divine?

Or instead, is it an honest conviction that our faith's dogma most accurately and coherently articulates the cosmological and ontological state of all reality, both now and in the past? I should hope for this option. For not only does it combine intellectual integrity with humility, but it offers sufficient elasticity with which to scrutinise our mythologies, to confront and resolve these exposed challenges, and in so doing to obtain ever better conceptions of reality and of our place in it.

The letter is written in Greek as we have no one who knows Hebrew [or Aramaic].I think the letter is a significant anecdote in that it reveals the extent of the Hellenistic influence in the region. For here is a military rebel leader campaigning on behalf of Jewish nationalism, while using a foreign language which represents the very antithesis of Jewish nationalism at the time.

Stop your ears, therefore, when any one speaks to you at variance with Jesus Christ, who was descended from David, and was also of Mary; who was truly born, and did eat and drink. He was truly persecuted under Pontius Pilate; He was truly crucified and died, in the sight of beings in heaven, and on Earth, and under the Earth. He was also truly raised from the dead, his Father having raised him up, as in the same manner his Father will raise up us who believe in him by Christ Jesus, apart from whom we do not possess the true life. — Ignatius of Antioch[73]

The Doctrine of Justification underpins an important theological schism that divides the Catholic tradition from the Protestant and Lutheran reformist traditions. All three traditions recognise the indispensable role of Jesus leading up to a sinner's restitution. But the Catholic tradition places an onus on the sinner to demonstrate repentance, such that atonement and grace are not automatic upon belief. The reformist traditions effectively absolve the sinner upon belief by insisting that belief implies repentance.

So Joseph could not have gone to Bethlehem for the census, because there was no such census at the time of Jesus' birth! Why then make the long trip on foot? Perhaps the motivation was to protect Mary from the embarrassment and ignominy of falling pregnant during the period of erusin (betrothal) prior to nissuin (marriage).

Luke is considered by many to be the most

factually accurate of biblical writers. But we

now know that even Luke's record of crucial

events is not without error. So we must

ask, Where does fiction end and fact begin?

And in seeking the truth, we must demand extraordinary

evidence when the claims for what is true are themselves

extraordinary.

Download PDF lessons-from-early-christianity.pdf (8.98 MB)