It is plain to see1 that Earth is endowed with a panoply of complex systems. A cocktail of gases fills the atmosphere. Earth's waters vary greatly in phase, salinity and mobility. Weather patterns vary widely over space and time, sometimes calm, sometimes turbulent. Even Earth's landmasses are in continual tectonic flux. And thanks to some primordial supernova event, the periodic table of elements is well represented here.

Biological complexity. But it is in Earth's biological systems that complexity is most prevalent. At all scales, from complex social interactions in whale communities, the subtlety of symbolism in humans, the sympathetic meshing of the many distributed processes making up a complete organism, down to the intricacy of the nucleic machinery in living cells, complexity in organic systems seems to be a defining feature.

Whence comes this biological complexity? A quick cursory glance might hint at the workings of an Intelligent Designer. By their very nature, biological systems appear so surprisingly complex that they could not have arisen by chance. Therefore, that they exist at all against all odds is taken as inferential evidence of the existence of a Designer, working creatively and proactively to imbue the world with complexity. In this way, life on Earth reflects the mind of the Designer. Life is made in the image of the Designer.

But are there other explanations for biological complexity—explanations which require neither Intelligence nor a Designer? Could it be that out of the rough and tumble of reality on Earth, biological complexity emerged naturally?

In seeking answers, I say we should steady our gaze, and look more closely. And for longer. For not only will we then be more inclined to discern patterns in the complexity operating across space and time, but we may discover underlying natural mechanisms by which complexity arose. This is the scientific endeavour.

Mechanisms matter. Ironically, surprisingly complex behaviour is often governed by equally surprisingly simple mechanisms. Simple thus begets a near imponderable complex. But these simple mechanisms invariably act in obscure ways. Who would have guessed the germ theory of disease, say? Invisible organisms playing a crucial role in mediating human suffering. And who would have guessed that physics offers mechanisms for chemistry, and chemistry for organic chemistry in particular? Organic chemistry, in turn, informs our understanding of the stability of organic compounds, such as peptide and saccharide chains?23

Who would have guessed that it is ultimately organic chemistry at work in genes which carefully mediates the complex growth of a developing embryo? Who would have guessed that the trait heritability of the elephant and the potato plant, say, are governed by yet another invisible object common to both, namely, the DNA molecule?

Evolution by natural selection is offered as a natural mechanism for the increase in biological complexity over time, leading to the radiation of life on Earth's occupying every available ecosystem niche, while allowing life to adapt in sympathy with changes in the environment.

Natural selection is not chance. Natural selection is not chance.

And because evolution is about natural selection, evolution is not about chance either. Neither Darwin, Dawkins,[1][2] nor any other evolutionary biologist that I'm aware of attributes the existence of biological complexity to random chance, akin to the flipping of a coin or the proverbial 12 monkeys randomly typing a novel.

Immersed in change. Biological systems are immersed in change. Climates change; dry seasons come and go affecting food and water supply; atmospheric carbon dioxide and oxygen concentrations fluctuate over time;[3][4] landmasses merge and separate in response to climate change and plate tectonics; ecosystems grow and shrink in spatial extent and in species richness and diversity. All the while, there is the ever-present threat of catastrophic volcanic and meteoric shock, such as what caused some of the five major species extinction events over the last 450 million years.[5] This disruption which is occurring at all scales is quite different to a coin spinning in a state of weightlessness, or a static array of typewriters.

It is in this context of change that organisms struggle to survive. Some do better than others. The ad hoc genetic variability within each generation confers selective competitive advantage to some members, thereby giving them a survival edge. That edge is inherited in the surviving offspring. And so species traits change over time. As the gene pool within an ecosystem evolves, organisms are able to exploit ecosystem niches with ever increasing nuance and refinement. But nothing is static. Change is thrust upon members of the ecosystem from within and without. And so species traits continue to diverge until new species emerge. As the biosphere evolves in this way, biological complexity ratchets up, step by incremental step. This is evolution by the mechanism of natural selection.[6]

Thus, as we contemplate the apparent irreducible complexity in biological systems, a tenet so central to the case for Intelligent Design, we must first consider what mechanisms may be at work. Proponents of Intelligent Design who appeal to the so-called argument from improbability[7] either ignore or do not understand natural selection as the mechanism for biological complexity. For such proponents, it is either design or chance.

But natural selection is not chance. Natural selection is not chance.

In the beginning. Since evolution by natural selection provides an explanation for the diversity and viability of life, what then of the origin of life itself, some 4 to 3½ billion years ago? Of course, natural selection requires that some basic genetic functioning be already in place. Variations in the gene pool must be heritable, for example. Natural selection cannot therefore account for the origin of life itself.

Were there natural mechanisms at work back then which scientists are now striving to discover?[8][9] Or did an Intelligent Designer mediate one last time immediately after the beginning, thus delegating control to some of the abovementioned forces? This seems implausible. Proponents of Intelligent Design who are prepared to accept evolution by natural selection still have to deal with problems in the Design itself. Exceptions to the rule and sloppy or ad hoc implementations seem to portray a less than perfect designer.

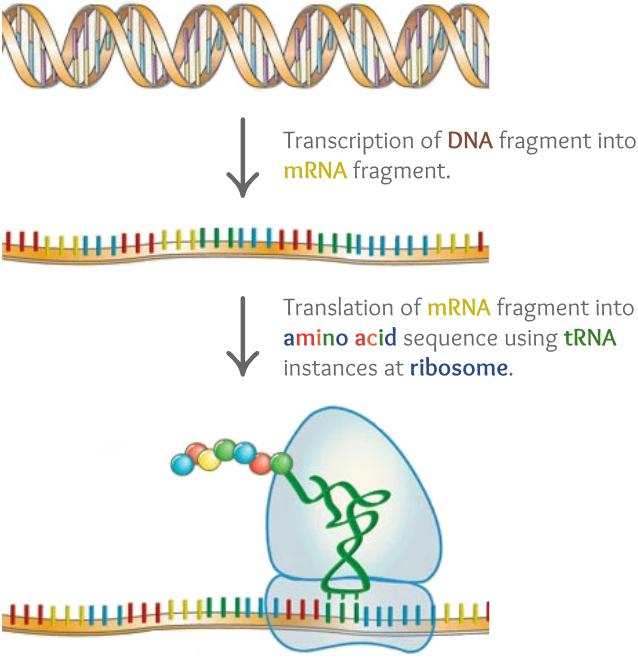

DNA molecule. Consider the genetic code as an example.[10] The genetic code is a map from DNA nucleotide4 sequences to amino acid sequences. The DNA nucleotide base pairs sequences are transcribed one-to-one into mRNA base pairs sequences. These mRNA base pairs then form triplets called codons which select for specific amino acids. Amino acids in turn are the basic building blocks for proteins. This building is done at the ribosomes5 within a cell's cytoplasm.6 With the help of specific tRNA molecules, the ribosomes translate the mRNA codons into amino acid, thereby forming proteins.

All life uses this same genetic code. Was this then a pristine design imperative implemented by the Designer? Not quite, for there are 32 exceptions.[11] The Blastocrithidia genus, for example, uses a different genetic code.[12]

Could another efficiency be the choice of DNA as a single molecule to encode for all life? Perhaps. Except that there are exceptions. Viroids, RNA viruses, and retroviruses do not contain any DNA.[13][14] And if we assert that viroids and viruses are not strictly alive because they do not metabolise, then are we really arguing that such RNA-based species do not fall under the ambit of Intelligent Design, while DNA-based species do? This cut-off is arbitrary.

Chromosome 2. Another problem with the Intelligent Design hypothesis pertains to chromosome 2 in humans. All primates except humans have 24 chromosome pairs in their genome.7 Humans have 23 pairs. There is evidence that in our evolutionary ancestry, our chromosome 2 became fused with a neighbouring chromosome. The evidence for this is compelling. Firstly, our chromosome 2 has a vestigial centromere8 section and two vestigial telomere sections.9 Secondly, at the putative fused section, our DNA coding sequence on chromosome 2 matches that on the chimpanzee's chromosomes 2p and 2q. For a Designer of important DNA sequencing such as on human chromosome 2, which is one of the longest of all human chromosomes, this all seems haphazard and ad hoc. Jacob Ijdo, whose work uncovered this, wrote:

We conclude that the [nucleotide sequence on chromosome 2] contains the relic of an ancient telomere-telomere fusion, and marks the point at which two ancestral ape chromosomes fused to give rise to human chromosome 2. — Jacob Ijdo, A. Baldini, D.C. Ward, S.T. Reeders, R.A. Wells[15]

Human genome. Aside from the genetic nucleotide sequencing which we share with chimpanzees and other primates, there appears to be nothing particularly special about the human genome when compared to the genomes of other eukaryote species.10 The human genome has roughly the same number of nucleotide base pairs11 (3.4 billion) as that of the house mouse (Mus musculus, 2.4 billion) and the domestic dog (Canis familiaris, 3.0 billion). It has about about 20000 to 25000 protein-encoding genes compared to the mouse's 30000 and the dog's 19000. Conversely, the genome of the marbled lungfish (Protopterus aethiopicus) has 123 billion base pairs. This is 40 times more DNA per cell than that of humans.

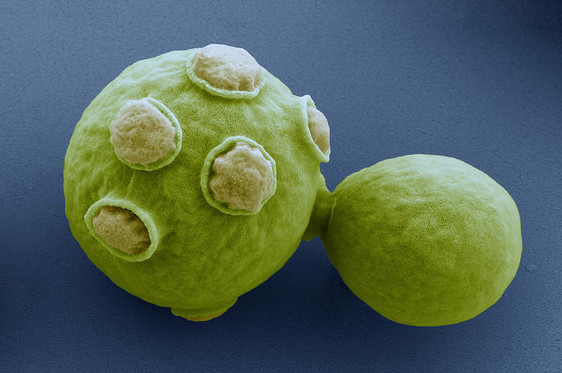

Gene expression. DNA functioning and gene expression do not seem to be orchestrated and intentional. Instead, they follow a mish-mash of ad hoc patterns, exactly as we would expect in natural processes. There is no clear association between genetic content and phenotypic12 complexity, for example. Between 25% and 50% of the genes in the genome of eukaryote organisms have at least one duplicate gene.[17] And sometimes there are many duplicates. For instance, the unicellular organisms called Stentor cells carry thousands of copies of their entire genome within the nucleus of their single cell.[18] And in interesting work carried out by Wagner,[19] it was discovered that yeast cells are able to compensate for the loss of entire genes for which no duplicate genes are available. Other dissimilar genes take over the functions of the lost genes.

Conclusion. The ad hoc exceptions in the genetic code, the ancestral vestiges in our chromosome 2, the non-spectacular character of the human genome, and the ad hoc nature of gene expression, should constrain our vanity in believing that out of all the species on Earth, including other primates, humans are endowed with some special Designer essence. Where is that special essence? It almost certainly does not reside within our DNA, a molecule which plays such a singular role in making us us.

For many, the urge to understand our complex world remains front and centre. Whence came complexity? And why? Once the mechanisms for abiogenesis are discovered—and I have little doubt they will be—the Hand of the Designer will most likely be sought and found elsewhere. For reasons which I might intuit, people see fit to cling tightly to that Hand, even though its reach grows shorter and shorter as the gaps progressively shrink.

Once upon a time, the spirit was on the wind in the willows. There was wrath and relief in the changing seasons. Voices from other worlds spoke from burning bush and thunder cloud. Then older and wiser men and women spoke of gods, of their walk and work, and of their desires and designs. Their godly hands reached down deep and wide. And with self-evident clarity and poise, they created a world within worlds as complex as ours.

Or so we are told.

Download PDF designing-with-dna.pdf (1.11 MB)